Oswald (c.604 – 642) is made known to us through the chronicles of Bede, although written a century later, in which he tells about the King who united the two kingdoms of Northumbria to become a powerful leader, who was generous to the poor and welcoming to strangers.

![]() Prior to an important battle, we are told that Oswald experienced a vision on a Constantinian scale of St Columba, who told him that God favoured Oswald. This understandably caused Oswald – and his army – to convert to Christianity and a victory was duly wrought over the King of Gwynnedd.

Prior to an important battle, we are told that Oswald experienced a vision on a Constantinian scale of St Columba, who told him that God favoured Oswald. This understandably caused Oswald – and his army – to convert to Christianity and a victory was duly wrought over the King of Gwynnedd.

Oswald requested help from St Aiden of Ireland in preaching and converting his Northumbrian subjects and according to legend, Oswald is reputed to have died at the battle of Maserfield at Oswestry (‘Oswald’s Tree’) where his dismembered right arm (which had been blessed by St Aiden) was taken by a raven into an ash tree. Having invigorated the tree, the arm fell to the ground, causing a healing spring to appear. Both the tree and the spring were soon associated with miracles.

Oswald is also known to us through a fragment of 12th century wall painting in Durham Cathedral, which is in the same niche and opposite to the well-known image of St Cuthbert. This may be no accident, as apparently Oswald’s head is in the same coffin as St Cuthbert.

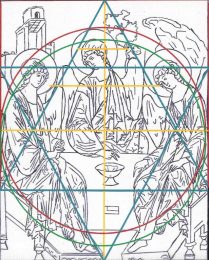

This image is based on a 13th century manuscript illustration.